The 1890 Treasury Note, also called a “Coin Note”, stands out as a unique chapter in U.S. monetary history. Authorized by the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890, these large-size notes were redeemable in gold or silver coin.

Their issuance marked a significant pivot from simple legal-tender notes to representative money—notes directly backed by valuable metal reserves.

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act and Its Tobacco

In July 1890, the Sherman Act mandated monthly Treasury silver purchases of 4.5 million ounces—nearly half of U.S. annual output. To compensate miners, the government released Treasury Notes redeemable in either gold or silver coin.

Known as Coin Notes, they were issued in high denominations ($1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100, and $1,000), quickly becoming notable for their distinctive metal-backing flexibility.

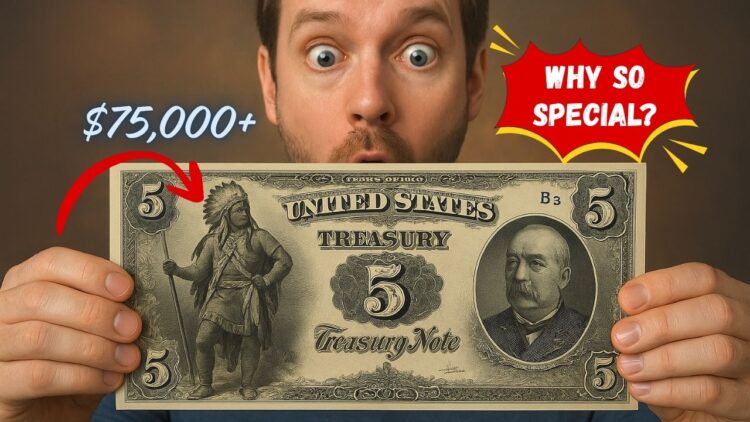

Bold Designs: Ornate but Controversial

The 1890 series notes are instantly recognizable for their elaborate reverse designs—so detailed they earned the nickname “busy backs”.

Treasury initially defended the intricate engravings as anti-counterfeiting measures, but critics argued they obscured security flaws. This led to a reversed shift toward simpler designs in the Series of 1891.

The “Grand Watermelon Note”: A Crown Jewel

The $1,000 Treasury Note (Fr. 379a/379b) stands out: its zeroes on the reverse are thick and green, resembling watermelon rind—earning the nickname “Grand Watermelon Note”. Only about 28,000 were printed, and just seven survive today. Auction history shows staggering value, topping $3.29 million in 2014.

Rare Survivors & Collector Census

Treasury Notes from 1890–1891 are exceedingly rare in uncirculated form. Surviving figures include:

- $100 notes: ~35 known; replaced in 1891 with “Open Back” designs.

- $1,000 notes: Only seven known, with the “Watermelon” variety being the most coveted.

- Other denominations: Many notes survive but appear mainly in circulated grades; uncirculated examples remain scarce.

1890 Treasury Notes Key Features & Value

| Denomination | Design Features | Estimated Survivors | Value Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| $1 | Busy back; Meade obverse | Dozens | VF–EF: $235–$800 |

| $2 | Red seal; James McPherson | Tens | Choice EF: ~$1,000+ |

| $5 | Busy back; George Thomas | Tens | CU: ~$2,000+ |

| $10 | Philip Sheridan | Tens | Choice AU: ~$3,000+ |

| $20 | John Marshall | Tens | Choice AU: ~$5,000+ |

| $50 | William Seward | Very few | Choice EF: ~$10,000+ |

| $100 | David Farragut; busy back | ~35 | Up to ~$200,000+ |

| $1,000 | Grand Watermelon design | 7 survivors | $1 million–$3.3 million+ |

The Transition to 1891: Simplifying Security

The Series of 1891 retained the metal redemption flexibility but simplified the back designs—earning the name “Open Backs.” This change reflected increasing concerns over visual and fiscal clarity and an ongoing effort to thwart counterfeiting.

Lasting Legacy of the 1890 Series

- Metal redemption flexibility: These notes could be exchanged for gold or silver—rare outside modern Federal Reserve Notes.

- Collector appeal: Detailed engraving, low survival rates, and high-denomination notes make them beloved among enthusiasts.

- Auction milestones: The Grand Watermelon note’s $3.29M sale, a historical milestone, underscores their value.

- Historic marker: Their story encapsulates late-19th century economic policy and early currency design evolution—just ahead of major reforms like the Gold Standard Act of 1900.

Why 1890 Series Notes Are Unique

- Coin-backing with gold/silver redemption

- Ornate currency art unlike anything before or after

- Extremely rare—especially in uncirculated grade

- High-denomination notes skyrocketing to multi-million-dollar sales

- Key stepping stone in U.S. currency evolution

The Series of 1890 Treasury (Coin) Notes represent a rare blend of artistry, metal-backed value, and economic policy in motion. Their ornamental designs, metal redemption flexibility, and dramatic rarity—especially the iconic “Grand Watermelon”—elevate them above ordinary currency. Today, these notes remain museum-worthy treasures and pivotal artifacts in the story of American money.

FAQ

Q1: What set the 1890 “Coin Notes” apart from other currency types?

Their redeemability in either gold or silver coin, tied directly to the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, was unique among U.S. paper money.

Q2: Why are the Series 1890 notes so rare in uncirculated condition?

Because of low original mintages and massive redemptions, few have survived in quality condition—especially high-denomination bills.

Q3: How much is a “Grand Watermelon” $1,000 note worth?

In 2014, one sold for $3.29 million, establishing its status as the most expensive U.S. currency ever sold.